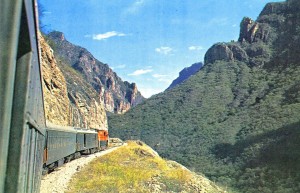

The Ferrocarril Chihuahua al Pacifico as it chugs through the Sierra Tarahumara. Photo postcard by Roberto Lopez Diaz.

My parents lived in Presidio, Texas when I was born. The then tiny town and its Mexican sister, Ojinaga, sit across the international border from each other on the Rio Grande—known as the Rio Bravo del Norte in Mexico. My parents were mostly bilingual and traveled easily “across the river” to shop or eat dinner. You paid the bridge owner small change and over you went. Driving on the rickety wooden bridge was more worrisome than any Border Patrol presence.

Presidio and Ojinaga were two sides of the same coin, but because Ojinaga was in another country, it felt romantic and otherworldly–a place where women wore brightly colored tiered skirts with white blouses pulled off shoulder, sometimes. We from the Rio Grande side were predominantly white and those from the Rio Bravo side were dark-eyed with black hair, and varying shades of brown skin. That’s the simple way this young girl saw the world.

I have always been completely comfortable in Mexico. Sure, I learned some things early — this would have been in the 1950s– that girls and women didn’t wear shorts on the streets of Mexican towns. Centered around block-sized plazas, villagers watched young people promenade Saturday evening while old people sat on the concrete benches, gossiping. A whitewashed Catholic church anchored at least one corner of the plaza, countered on another corner by a hotel. A guitar or accordion played in the distance, and you might hear roars from a bullfight. American Anglos prized Mexican bread and Carta Blanca beer, and the seafood trucked to Ojinaga from the Pacific was the only decent seafood anywhere in Far West Texas. Presidio had a plaza too, but no bullfights or seafood.

When I was 16, my parents were taken with the idea of taking the Ferrocarril Chihuahua al Pacifio west from Ojinaga across the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains of northern Mexico. The train traverses Copper Canyon, deeper in some places than even the Grand Canyon. Named not for the mineral, but for the color of sunlit cliffs, Copper Canyon was still home to few cave-dwelling cultures. Passengers travel 8,000 feet down from the canyons to sea level on the Gulf of California coast.

Leaving the Chihuahuan dessert in July is a welcome break, and at our first stop we disembarked at what my parents called Chihuahua City, staying the night at the Hotel Palacio Hilton. The souvenir stationery I kept lists Conrad N. Hilton as the chain’s president. More used to my grandmother’s version of yellow cheese enchiladas served flat with a fried egg on top, I wasn’t prepared for the dark red mole sauce on or near every dish at the Hilton’s dining room, and I became tourista ill, my rude introduction to leaving the border for the interior of Mexico.

I counted 77 tunnels through the Sierra Madre, often looking back at a curve where the end of the train hadn’t even entered the tunnel we were leaving. At a cost of $800 million, the brilliantly engineered railroad took 60 years to build. Today, I wonder if it was worth all those millions. Then, leaning out the half-open railcar doors to feel the cool air left me covered with black arms and face as the old diesel engine burned oil in its wake.

But the precarious cliffs and tight tunnels are not the memory I’ve carried 49 years. Through the windows looking into the wilds of Mexico, I peered into faces of children who looked like me. I had freckles and hair the color of barbecued potato chips. Running next to the slowing train were children also with red or yellow hair, freckles, and even blue eyes. All my suppositions about Mexicans flew out the train window and away with the smoke. We were in an area settled by German-speaking Mennonites who have been farming around the canyons, specifically Cuauhtémoc, since the 1920s.

The train chugged through scattered communities inhabited by the Tarahumara, indigenous people made famous by a 2008 book about their low mortality rates and barefoot-distance running. When I saw them, men wore zapetas or loincloth and oversized colorful blouses, and women wore ribbons in their hair and several skirts on top of each other. These people who escaped 500 years ago from enslavement in the Spanish mines are now falling victim to drought, modernity, and a few ruthless cartels that use them to carry drugs. The Tarahumara are currently in a struggle with the logging industry to preserve their homeland.

The trip ended at Los Mochis, and we traveled by taxi to the fishing village of Topolobampo. The ocean, the railroad, the stunning tunnels and bridges—none of that is as valuable as learning you can’t make assumptions about people, not even neighbors.

That 1964 photo is FABULOUS! Quite the fashionista. Nice post.

Love the picture. I remember when we used dress up to travel. Sounds like a great train trip. Is it still running?

I think so. Not sure what kind of shape it’s in…

Thanks for reading!

I had no idea that your parents were bilingual nor that you had grown up so near the border. Do you still speak Spanish? Digame, por favor.

Leslie, sadly, I do not. I understand it okay, but that’s it. We moved away from Presidio when I was five. But in that part of Texas you’re never that far from Mexico.

Thanks for reading.