Traveling Texas Highway 118 from Alpine to Fort Davis is Western eye-candy and guaranteed to fire up your imagination. After a flat stretch leaving Alpine, you encounter towering rocks on both sides of a curvy, climbing state highway. It’s the kind of road where you think, “Apaches could hide behind those rocks.” Or maybe you only imagine that if you grew up watching 1950s-era Westerns or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

In Fort Davis, you find more going on than its tiny size suggests. The night we visited, the Hotel Limpia featured live music under the patio’s big-leaf trees. The Transpecos Blend had a local legend, Washtub Jerry, wearing garden gloves and strumming a washtub bass. At Prude Ranch outside of town, telescopes are propped up next to RVs for the annual Texas Star Party.

Through one of the restored officer’s quarters at Fort Davis Historic Site. The kitchen was separate from the main house because of fire danger. Photo by Taylor Heldfeldt Jones.

A first-time visitor in our group requested a visit to the original reason for the town: the actual fort, used during the Indian Wars until the 1880s. It’s north of town, barely, and barracks, officer’s quarters, and the hospital have been carefully restored. In 1961 Fort Davis was declared a National Historic Site.

It’s a spot I visited often as a girl, but now I have issues. Well, one issue. Not with the general history of the fort, only a most specific story that caught my interest years ago.

Not a lot of feminine heroines populated my imagination or anyone else’s in the 1950s—Elfrida Von Nardroff, later-disgraced game show winner, and NBC’s Pauline Frederick, whose face I could hardly see on a snowy TV while she reported from the United Nations. Yeah, and Nancy Drew, but she wasn’t real.

So it was with great curiosity and enthusiasm that I latched onto Indian Emily, a local girl whose grave was on the grounds at the Fort Davis. Reading the Centennial marker sent my imagination soaring: “Here lies Indian Emily, an Apache girl whose love for a young officer induced her to give warning of an Indian attack. Mistaken for the enemy, she was shot by a sentry, but saved the garrison from a massacre.”

Another part of the story, as told by Fort Davis newspaper reporter Barry Scobee, was from a military report. In a sort of reverse Cynthia Ann Parker tale, the child Emily was wounded in battle, rescued by soldiers, and raised by a post officer’s family. She fell in love with the family’s handsome son, was not allowed to marry him, and returned to her people.

Upon learning her Apache tribe planned an attack on Fort Davis, she sneaked away at great risk and warned the young soldier. Or something like that. As it turns out, my story is as good as anyone’s in this case.

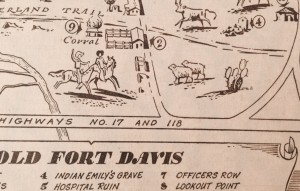

According to old-timers, Emily’s grave at one time had a crude marker: “Indian Squaw – Died by Accident.” But a proper marker was later installed, postcards made, and a map of the fort, including Emily’s grave was in the newspapers when the fort was declared a National Historic Site.

As a sixth-grader, I stuck the postcard in my scrapbook, writing under it, “My Favorite”, and moved on through school and off to college, looking and finding plenty of role models by then.

Upon the US Senate’s vote to declare the frontier outpost a National Historic Site, The Fort Worth Star Telegram published this sketch August 30, 1961.

Historical mischief was afoot in 1969 in the person of reporter Mike Cox of the San Angelo Standard Times. Cox went sleuthing about and wrote that the Indian Emily story was untrue. According to his source, no less than the Site’s superintendent, records do not exist of Tom Eason, the soldier Emily fell in love with. Further, “her behavior” in battle was very “un-Apache”, and captured Indians were usually sent to boarding school, not kept “around the forts.”

And in a mostly offensive statement, the superintendent offered that someone had “dreamed up the story after reading one too many Victorian romances.”

Soon after Cox published his findings, the National Park Service removed the piled stones from the grave and put the historical marker in a closet.

Scobee gets credit for the Indian Emily story having whatever ever legs it did. Cox writes that Scobee always believed some truth hovered over the story. In my own reporting, I’ve had some issues with Scobee’s versions of truth, but usually, I’ve found he’s in the ballpark or hovering above it.

The old saying goes that history is written by winners. In this case, I wonder how much, if any, serious historical research exists about adolescent Apache girls. Until the last half of last century, history focused on male interests and achievements. And individuals were stamped with a group identity not always allowing for individual human nature.

Fifty years later, I want Emily’s story to be true. It’s the story of a brave Native American girl from my small part of the world. Mark Twain wisecracked, “Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please.” There is no one way for an Apache girl to behave in battle, so I choose to believe Indian Emily’s story.

I too choose to believe as well. Thank you for the picture and the story of a young brave girl.

Thanks, Karen.

Miss you.

I feel sorry for people who cannot grasp the tail of a happy ending stories and hold on. Where would we be without Superman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman…………………………………??

As a journalist, I have to say part of the job is ferret out the truth. So I can’t really get too upset with Mr. Cox. I am just a skeptic by nature. I blame Clarence. He always said, “Think for yourself.”

I like my “facts” with a heaping dose of great Texas storytelling!

Thanks, Patty!

Great story! Great writing! Loved Mark Twain’s quote!

Thanks, I’d not heard this story.

I have been reading some of Bryan Woolley’s old columns tonight, thinking about him and how much I have loved his writing; in one of them he reminisced about Barry Scobee and his influence on Bryan’s life. Something just drew me back to your writing after that. Thanks for writing this. I loved the story of Indian Emily, loved visiting the site and reading the story, and for me, it will always be true! Nancy

I’m sad about Bryan, too. I still have an old, yellow newspaper story he wrote about some of the historic houses in Fort Davis, one of which was his. Thanks for reading. One good way to start a good discussion among writers of a certain age in FWT is to bring up Barry Scobee.

I am 62 years old, 63 in two weeks. I stood at Emily’s grave when I was ten, as my dad told me the story. I was devastated when I saw a few years ago that her grave was gone. I write songs as a hobby, and I felt compelled to write something about this. It is posted at cd baby.com and can be heard in it’s entirely without purchasing it. It is also free on Jango.com.

Wow. Thanks so much for sharing this.

I too as a child was taken with the story of “Indian Emily”, in the tragedy of the entire story. As my parents and I visited Fort Davis in the 1970s, her story always made the biggest impression. On Saturday, I revisited the fort for the first time since I was 12 years old, and took the tour, looking mainly for Emily’s grave, but was disappointed to learn they had removed her headstone and gravesite. As a writer, I decided to do some investigation as to why and found, as you all mentioned, the Park Service feels this is a fictional story. But during my digging, I came across this notation made by William Henry Gardner, Post Surgeon from 1882-1886:

“A cowardly and brutal murder of an Indian captive (squaw) was perpetrated by some party or parties unknown near the hospital where the woman was tented. The deed was done with an axe or some other sharp object – her head being split open, and rape appears to have been the object.” This report was written in 1882 is in the medical history of Fort Davis on page 329.

The Apache were considered to be “savages” in those times and an act like this described above would be of no real consequence except if it were committed by a well-known soldier and word of it could damage his career. Since I believe Emily was brought to the fort and reportedly helped by one of the hospital staff, she would most likely be housed near the hospital. Our Emily may have an even more tragic story than we know and it’s being covered up with a romantic story to hide this atrocious act.

I believe Emily was real and I pray she is not the poor victim above, but unfortunately, I have a gut feeling she may have suffered this horrible fate.

What do you think?

Thank you, Donna, for reading. In the years since I wrote about Indian Emily, I have become more convinced there is some truth to the story. I have a friend in San Angelo who has done exhaustive research on the Native Americans of West Texas, and while he hasn’t specifically researched this story, he has quite a library of copied handwritten letters/journals detailing all matter of kidnappings and so forth that took place in the mid to late 1800s.

I agree completely with your conclusions.

What do you write about?

The Indian Emily marker should be returned to her grave site – it should never have been removed. Whether the story about Emily is true or not, the story came from somewhere and it should be kept in the context of the western legends that came down through the history of our country. How about it National Parks? Put back the marker where it came from – on her grave.

Thank you for reading and for the comment. I have since learned that some state governments did send young Native Americans to boarding school, but mostly in the midwest. The story could use a more scholarly treatment than I was able to give, but I still like believing it.